Chapter 2 - Essential Memory Techniques

You are reading an online version of The Chess Memory Palace by John Holden.

Copyright © 2022 John Holden, all rights reserved.

Click here to return to the online contents page.

For the best reading experience, you can buy

the paperback or

the ebook.

Subscribe to

@ChessMemoryPalace on YouTube

for video tutorials.

You are reading an online version of The Chess Memory Palace by John Holden.

Copyright © 2022 John Holden, all rights reserved.

Click here to return to the online contents page.

For the best reading experience, you can buy

the paperback or

the ebook.

Subscribe to

@ChessMemoryPalace on YouTube

for video tutorials.

Amazon links are affiliate links — this gives me a little bit more for each sale, at no cost to you. I earn from qualifying purchases.

Take your time if it is all proving too difficult. Loosen up with some stretching exercises; flex your memory; touch the toes of your imagination with a few fantasies.

Dominic O’Brien, Eight-time World Memory Champion

If you are now presented with picture notation, you can understand it and play the right move at the board (Chapter 1). The next question is, how do you memorise the picture words?

In short, we will use our naturally great memory for places, images and stories. We will use our imagination to link each picture word pair to a location, in a miniature story. For example, we will visualise the picture words heart and sponge as “a heart using a sponge to clean the outside of an aeroplane". We will be creative to make this little story as compelling as possible. We will then use a sequence of locations to create an ordered structure of memories. This is called a memory palace.

In Chapter 3, we will discuss how to select picture words and how to design a memory palace. For now, I assume we have already been given the picture words and locations that we want to memorise.

What makes things memorable?

Before we construct our first memory palace, let’s consider what makes something memorable.

First, it almost goes without saying, we remember things better when we pay attention. The reason we often mislay our keys or phone is because we were thinking about something else when we put them down. Simply making a conscious effort to notice where we place an object makes a big difference. So, pay attention! When you visualise1 images, take the time (without multitasking) to concentrate on the scene: the colours, sounds, smells, tastes, feelings, shapes, textures. This already goes a long way to creating a lasting memory.

Second, we remember things that grab our attention – and things that grab our attention tend to be surprising, funny, and, well, in the way. Typically, in any given situation, we have an aim, and we particularly notice the objects that help us achieve this aim (tools) or that get in the way (obstacles). If something sits unobtrusively to the side of the path, we are unlikely to see it at all, let alone remember it later. If the same object lies on the path itself, we are more likely to see it. If it jumps up and down and shouts, we cannot ignore it. When we memorise images in our memory palaces, we need fill our path with bold, exaggerated, movement-filled scenes.

Third, we find it easier to learn information when we already understand the context. You will remember a piece of trivia about a celebrity you know more easily than learning the same piece of trivia about another celebrity you have never heard of. When learning a language, it is easier to learn three new words by studying three example sentences, each of which introduces one new word at a time, rather than trying to learn all three words in a single model sentence. All recall is association, connecting one context with another, so it is easier to learn something when you already know half the story.

As humans, we are particularly good at remembering places. Even if you think you are bad at following maps (which is a different skill), you can find your way to work or the local shops without trouble. If you have ever listened to an audiobook while walking around, you may have noticed that you can remember your location when you listened to a particular chapter. The story in the chapter triggers your memory of the place, and imagining the place triggers your memory of the story.

When we store images in a memory palace, we are being deliberate about the associations we create. We are taking advantage of our natural memory for places by consciously linking the information we want to memorise (chess moves) with familiar places.

Picture words as characters

Now let’s apply these principles. In this section we will create bold visualisations of individual picture words. In the following section we will associate two picture words together in a location.

Many picture words are naturally compelling. It is not difficult to imagine a shark (f4), for example. But let’s practise anyway, as a warm up.

Imagine a great white shark, perhaps the shark from the film Jaws. Imagine its strength as it powers its body through the water, the sound of the waves, its sharp white teeth. Imagine its gaping mouth and your fear (thrill?) as you watch it. What does it feel like as it bites you?

It is not pleasant to be bitten by a shark! But this makes the point that your images should be vivid and compelling. The best will make you laugh or physically react. You don’t always need to “break the fourth wall” and participate in your images, but you must always feel like they are right in front of you, not watched passively on a screen. Think theatre, not cinema.

Other picture words are a challenge. For example, the one-syllable picture word for e4 is lore (a body of knowledge). How can you visualise an abstract concept like lore? I imagine a book of lore. A book is not a memorable object either. It is small and rectangular and unremarkable. But one book from J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series is very memorable:

Harry just had time to register its handsome green cover, emblazoned with the golden title The Monster Book of Monsters, before it flipped onto its edge and scuttled sideways along the bed like some weird crab. […] “Ouch!” The book snapped shut on his hand and then flapped past him, still scuttling on its covers. Harry scrambled around, threw himself forward, and managed to flatten it. Uncle Vernon gave a loud, sleepy grunt in the room next door.

Note how many senses are used: the visually bright cover, the sound of the book scuttling and flapping, the pain as it snaps on Harry’s hand. Most important of all is the story of Harry hunting the book around his room while trying not to wake his uncle. These all combine to make a very compelling description. When I visualise lore, I imagine The Monster Book of Monsters.

Children’s TV is also a good source of images. This is because it expresses objects in simple and bold form, and anthropomorphises liberally. It is not unusual to see a talking coach (g6), machine (c6), or even a dinner plate (dish, a6). You can turn pretty much anything into a character by adding limbs and a face.

While you are watching TV, take note of the adverts too. Marketing agencies spend vast sums on market research and focus groups to create adverts that conform to the principles of memory: often funny with surrealist humour, multi-sensory, and using relatable characters to represent a faceless company. Think of the Michelin Man, Tony the Tiger, or the Pillsbury Doughboy.

As you build your memory palaces, your picture words will become recurring characters that you see again and again. This makes them easier to remember. The first time you memorise lore, it will take some effort to make a compelling picture. The second time, it will be much quicker. Soon you will be creating pictures fluently.

Robust composite images

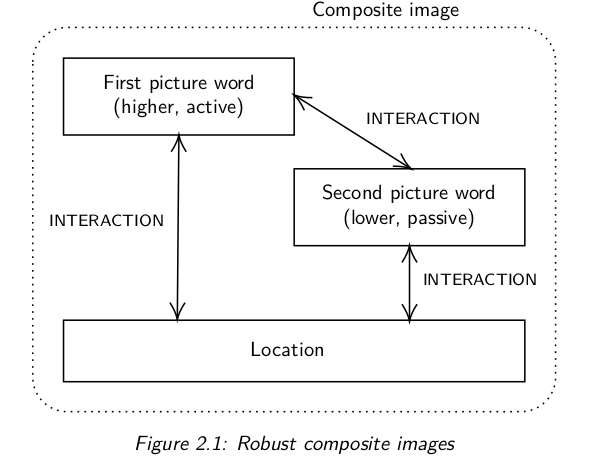

Picture words are characters. Characters act in stories. We are going to place each picture word pair in a location, then craft a little one-scene story to memorise it. I call these stories composite images, because each one is composed of three elements: the first picture word, the second picture word, and the location.

We create strong associations by imagining clear interactions between the first picture word, the second picture word, and the location. Making these interactions compelling is even more important than making the characters compelling, because this is how you move in your mind from the location, which you already know, to the picture words. You need to visualise three interactions: (1) the first picture word with the second picture word, (2) the first picture word with the location, and (3) the second picture word with the location. See Figure 2.1.

For example, let’s say you need to memorise a tree (first picture word) and alpaca (second picture word) in an aeroplane cockpit (location). Hopefully you are already imagining the tree and alpaca as vivid characters. The tree is an old, gnarly oak tree, waving its branches like arms and its roots like feet. Perhaps you are visualising an Ent from J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings or a talking tree from C. S. Lewis’s The Chronicles of Narnia. The alpaca meanwhile is soft and fluffy with a big smile on its face.

Now you need to visualise the three interactions: (1) the tree with the alpaca, (2) the tree with the cockpit, and (3) the alpaca with the cockpit.

-

Recall from Chapter 1 that the first picture word should be doing an action to the second picture word, or using the second picture word as a tool. The first picture word should also be positioned higher than the second picture word. In this case, I imagine the tree riding the alpaca. The tree roots are wrapping tightly round the alpaca’s belly, and two of its branches are holding on to the alpaca’s head, covering the alpaca’s eyes with leaves. The tree and alpaca are working as a team to reach all the controls.

-

The tree is reaching up with its other branches, pressing the buttons on the cockpit’s ceiling. Some twigs are scratching the windscreen glass.

-

Meanwhile the alpaca is using its hooves to press the pedals, with a sharp clacking sound, and its nose to push the throttle.

When you imagine entering the aeroplane cockpit, it should trigger your memory of the tree and alpaca. The tree is interacting with the ceiling controls, the alpaca is interacting with the floor controls, and the tree is interacting with the alpaca.

In theory you would only need two interactions, not three. The location could remind you of the first picture word, which reminds you of the second picture word: so strictly speaking you don’t need to link the second picture word with the location. However this would leave you vulnerable to any lapse in memory. After six months without review, under the pressure of a strong opponent and ticking clock, maybe you will forget one of the three interactions. But as long as you recall the location and two of the three interactions, you can triangulate to access both picture words. By visualising all three interactions instead of just two, you have added redundancy, which makes the image more robust in your memory. In effect, you need to recall only 66% of the image to recover 100% of the information.

In the same way, the more detail you put into each of the three interactions, the longer they will stick in your mind. The alpaca is pressing the pedals with its hooves and pushing the throttle with its nose. Each additional detail makes the image safer in your memory, and the less often you will need to review it (Chapter 7). It is helpful to “visualise” the interactions with multiple senses: imagine the feeling of the scratched glass and the sound of the alpaca’s hooves.

Practice

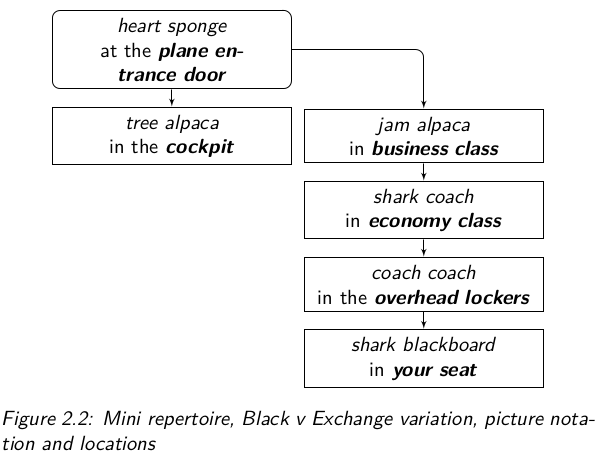

Now let’s memorise a small repertoire, in the setting of an aeroplane. We will practice memorising Figure 2.2, which is a subsection of the Spanish Exchange Airport memory palace in Chapter 5.

I will refer to diagrams like Figure 2.2 as “tree diagrams”, because they follow a branching structure. We begin at the plane entrance, and then choose one of two paths. Don’t worry about the shape of the arrows. It is not significant that some are longer or curved; that is just to fit the diagram neatly on the printed page.

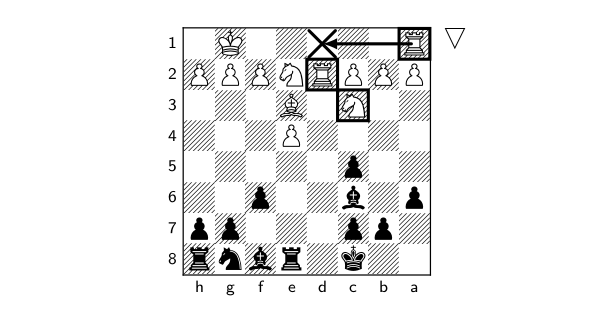

By the way, you don’t need a chessboard to memorise Figure 2.2. But, in case you are curious, Figure 2.2 picks up the repertoire in the position below, with White about to play heart (13.Rad1).

I am going to describe six composite images. Take your time. Imagine the stories in as much detail as you can. Don’t worry about memorising, just let your creativity flow.

- The memory palace begins at the plane entrance with the picture words heart and sponge. Instead of a flight attendant greeting you, the airline has tried to show a warm welcome by employing a heart. The anthropomorphic heart has little arms and legs; it stands in the doorway, beating rhythmically, holding the edge of the door. The heart is welcoming passengers aboard with a giant sponge. It uses the sponge to clean their faces and clothes, then turns to shining the outside of the plane until it sparkles. Unfortunately the heart is not very hygienic, some blood is pumping out onto the sponge and getting wiped onto the plane. The heart greets you as you walk on by sponging down your face. You feel the roughness of the sponge rub the skin on your nose.

In this case the sponge was the second (passive) picture word and I find its texture memorable, so I didn’t actively turn it into a character. If it were the first picture word, I would make more of an effort to anthropomorphise it; perhaps turning it into a sea sponge with little eyes, or even replacing it with a children’s TV character who likes cleaning things.

After entering, you can turn left to the cockpit or right to the main body of the plane. First let’s go left.

- Entering the cockpit…can you remember what you see? Re-read the previous section if you need to.

Now instead of turning left, let’s go back to the entrance (after passing the heart and sponge) and turn right instead. You are going to (1) walk through business class and (2) economy class, then (3) put your luggage into the overhead lockers, and finally (4) sit down in your seat. This sequence of four locations completes the aeroplane memory palace. I have drawn a map of the aeroplane in Figure 2.3.

- You enter business class. One of the executives has tried to show off her wealth by bringing aboard expensive jam and her pet alpaca. For a moment, the jam jar is balancing on the alpaca’s back…until it wobbles and tips and empties itself all over the alpaca. The alpaca’s soft white fur becomes sticky and clumpy as the sweet-smelling jam trickles down its flanks. The jar itself falls to the floor with a crash and breaks into shards of glass. The alpaca careers wildly around the small space, treading on handbags and rubbing jam onto the seats and onto the shocked executives’ fancy suits. You try to rush past to get to economy class, but can’t help brushing the alpaca and getting jam on your shirt.

-

You pull aside the curtain and enter economy class. This location is just as chaotic. A shark evidently did not want to wait for its in-flight meal; it has taken control of a toy coach and is driving it up and down the aisle, snapping at passengers’ legs. The shark holds the steering wheel with its pectoral fins and flaps with its tail. Heavily weighed down, the coach engine roars and its tyres leave a track behind them.

-

Tiptoeing gingerly around the shark and coach, you open the overhead locker to deposit your luggage. Ouch! Your hand is caught between two toy coaches. (Picture words: coach and coach.) They are repeatedly reversing, revving their engines, then charging into each other like rutting stags. It seems two children have packed toy coaches in their hand luggage, but the coaches are territorial and don’t like sharing the locker. Their headlights and registration plates are contorted into angry faces, they lock their windscreen wipers like antlers, and their windscreens begin to crack from the repeated impacts. Exhaust belches out of the locker, making you cough.

Note that when a composite image contains two of the same picture word, you don’t need to worry about one being active and one being passive. The coaches can fight as equals.

Note also my attempt to explain the image. Why are the coaches there? This gives the illusion of understanding. We remember things better when we understand them.

- At last it is time to sit in your seat. But what is this? A shark is sitting there already. (Why visualise the shark in your seat, rather than the seat next to you? Because now the shark is breaking a social contract, which creates strong emotional resonance.) Perhaps the shark sat in the wrong seat because it can’t read its ticket. It is learning to read by writing with chalk on a blackboard that has replaced the in-flight entertainment screen. The shark is straining against its seatbelt, leaning forward with a look of intense concentration on its face, balancing the chalk between its fins, scratching the chalk across the blackboard. You have no patience for more delays, so you unbuckle the shark and wrestle it out of your seat. It fights back by bonking you on the head with the blackboard.

…and that’s it! You have finished learning your first memory palace. Close the book, take a pencil and paper, and try to draw out the tree diagram. The aim is to lay out your 12 picture words in six pairs, and in the right structure. If you like, sketch the images as well – you don’t have to show anyone! Take your time to walk through the whole aeroplane and visualise the composite images afresh. Feel free to add your own details and change the stories to your liking, as long as you preserve the picture words in the right order.

Learning from mistakes

How did you do? Many people are surprised at how much they achieve on the first try. Memory palaces build on our natural memory for places and stories, so it doesn’t take much practice before you can achieve amazing things. If you remembered all 12 picture words in the tree diagram, congratulations! If you forgot some, don’t worry: this is the most interesting part, where you learn how your own memory works.

Don’t think of mistakes as random errors where you need to “try harder” or had a “naturally bad memory”. Ask yourself, what caused the problem? Mistakes come for one of five reasons.

-

You missed a location entirely. For example, maybe you jumped straight from the entrance to economy class, and forgot about walking through business class. The solution is to make the memory palace structure clearer in your mind. Watch a video of someone boarding an aeroplane, or just visualise it again carefully. You may need to open up “lines of sight” between the locations, for example make sure all doors are open and curtains are drawn back. Another tip is to have the locations bleed into each other, for example the (jam-covered) alpaca could stumble to the boundary between business and economy class, where it sees (or even interacts with) the shark and coach.

-

You forgot one of the two picture words in a location. For example, maybe you arrived at your seat, saw the shark, but couldn’t remember what it was doing. This means you forgot two interactions: the shark with the blackboard, and the blackboard with the seat. Concentrate on rebuilding both interactions. Perhaps the entertainment screen smashes to reveal a blackboard underneath. Visualise the shark leaning forward and scratching away at the blackboard with chalk. If you repeatedly struggle to recall a picture word, you might need to create a new story that is more memorable to you. Make it dramatic, funny, or even grotesque.

-

You couldn’t remember either of the picture words in a location; the location was empty. For example, maybe you imagined passing the curtain into economy class, but couldn’t remember anything that happened there. This again means you have lost two interactions: between the location and the two picture words. In this case, the solution is to make sure the location has a clear “hook” (or two) – something for the picture words to interact with. For the economy class location, I use the floor (which connects to the tyre tracks of the coach) and the passengers (which connect to the biting shark).

-

You couldn’t remember the order of the two picture words within a composite image. For example, how do you know whether the order is heart sponge or sponge heart? The solution is to ensure you have a clear active and passive relationship between the two picture words, and that the first picture word is positioned higher in the scene. The heart is using the sponge to clean the plane and passengers. It is a tall heart, leaning down to reach your face.

-

You could recall an object, but you didn’t know what picture word it represented. For example, perhaps you could visualise the tree riding something animal-shaped and furry, but you didn’t know if this was an alpaca or a llama. One solution is to adjust the picture to be more specific, for example giving the alpaca straight, pointed ears – and involving these ears in the interactions. However the better solution is just to remind yourself of the right answer and continue building memory palaces. In Chapter 3 we will discuss selection of picture words and the importance of being consistent. Simply put, I often use the picture word alpaca in my memory palaces. I never use llama. (I use lemur as my two-syllable picture word for e3 instead.) So I never worry about what the alpaca-like animal is: it must be an alpaca, because llama is not an option.

If this worries you, remember that the board itself will validate or invalidate your picture words. Alpaca is a sensible move in the position, 14...Ne7. Llama is impossible: no black piece can move to e3. It is extremely rare for a misremembered picture word to be a sensible move.

When you forget a composite image, try not to get frustrated with yourself. Identify why you forgot it, then fix the problem. Like most things, this gets easier with practice.

Moving on

This chapter has taught you creative memorisation. These techniques are sufficient to memorise every composite image in the book.

At this point, you may think this is a lot of effort, and wonder whether it is easier to drill opening moves the traditional way! Let me reassure you that memory techniques are worth the trouble. Memory palaces can be expanded with virtually no limits, and the time investment scales almost linearly, unlike learning new facts through pure repetition. It takes a long time to write all this out, but your mind can process images much faster than words.

The purpose of The Chess Memory Palace is to apply memory techniques to chess, not to dive deeply into memory techniques themselves. If you would like to know more, I have suggested further reading in the Notes at the back of the book.

Now you know how to convert picture notation into chess moves, and you know how to memorise a structure of composite images in a memory palace. It is time to become a memory palace architect.

-

Although I speak of “visualisation”, don’t worry too much about how clearly you can “see” the images. People have different internal experiences. Notably, several successful mnemonists report that aphantasia (being unable to form mental imagery) does not prevent them imagining scenes and building memory palaces. ↩

Watch on YouTube

Watch on YouTube