Chapter 3 - Memory Palace Architecture

You are reading an online version of The Chess Memory Palace by John Holden.

Copyright © 2022 John Holden, all rights reserved.

Click here to return to the online contents page.

For the best reading experience, you can buy

the paperback or

the ebook.

Subscribe to

@ChessMemoryPalace on YouTube

for video tutorials.

You are reading an online version of The Chess Memory Palace by John Holden.

Copyright © 2022 John Holden, all rights reserved.

Click here to return to the online contents page.

For the best reading experience, you can buy

the paperback or

the ebook.

Subscribe to

@ChessMemoryPalace on YouTube

for video tutorials.

Amazon links are affiliate links — this gives me a little bit more for each sale, at no cost to you. I earn from qualifying purchases.

Though for Mma Potsane the landscape, even if dimly glimpsed, was rich in associations. Her eyes squeezed almost shut, she peered out of the van, pointing out the place where they had found a stray donkey years before, and there, by that rock, that was where a cow had died for no apparent reason.

Alexander McCall Smith, Tears of the Giraffe

In Chapter 1 we learned to convert picture words to chess moves, given the memorised images. In Chapter 2 we learned to memorise images, given the palace structure and picture words. In this chapter we will learn to design the palace structure and select the picture words, given the repertoire.1

This process starts by drawing out our repertoire as a tree diagram. We then choose a general setting, such as an airport or school, and map out the tree diagram onto the setting. Finally we populate the locations with picture words, so that they ready to memorise with the techniques of Chapter 2. This process creates a branching map: as you mentally travel through the memory palace from location to location, you face a series of junctions where the path splits.

If this sounds strange, remember that you already use a branching map on a regular basis. When you leave your home to go to the doctor, perhaps you turn right. When you leave your home to go to church, perhaps you turn left up the road, then turn left again. When you go to the beach, perhaps you turn left up the road, then straight on to the motorway.

Don’t worry if you don’t follow everything at first. We will see two extended examples in Chapters 4 and 5.

Drawing a tree diagram

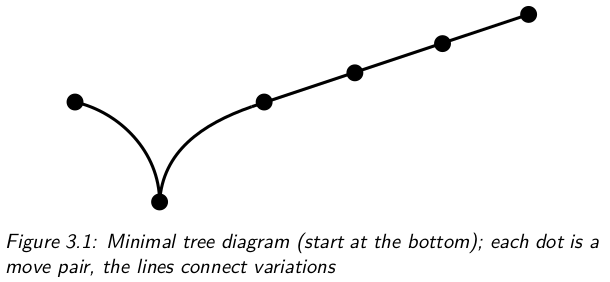

Before you design your memory palace, you need to know what the shape of your repertoire looks like. So the first step is to draw out your repertoire as a tree diagram, with dots or boxes to show the move pairs, and lines to connect the move pairs into variations.

We already saw a small tree diagram in Figure 2.2, but don’t worry about labelling the move pairs (in algebraic or picture notation) just yet, and don’t worry about making it neat. At this stage I usually draw the tree as as a series of dots and lines, like Figure 3.1. This is much easier by hand than on a computer.

In Chapter 5 I will cover transpositions and options for both colours. For now let’s assume your repertoire has no transpositions, and you have only one prepared reply for your opponent’s moves – in other words, you haven’t prepared any options for yourself – so your repertoire is a simple tree.

Choosing a setting

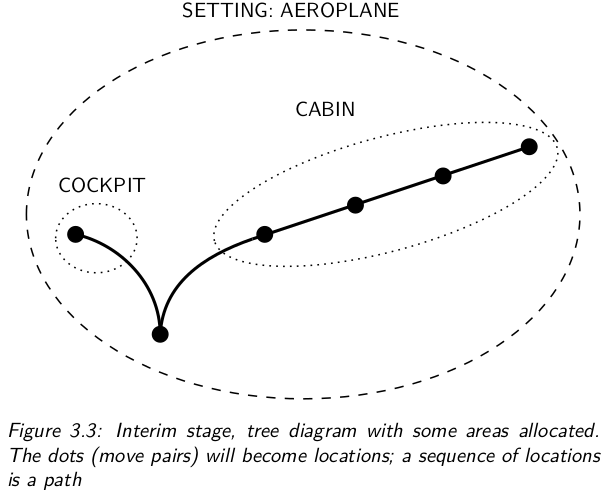

Next, you need a setting for your memory palace. The setting is the general area where you will place your locations. In Chapter 2 we saw six locations in the setting of an aeroplane. In Chapter 5 we will extend this to 35 locations in the setting of an airport.

A good setting is a place you know well. You should be able to close your eyes and navigate around it, picking out tens if not hundreds of unique locations. It also needs to be complex enough to fit lots of branching paths. One long corridor will be fine for a forced sequence of moves, but won’t be a great fit if you need to add variations.

Chapter 4 uses the setting of an urban transit line. Other obvious settings are your high school, college, workplace, neighbourhood, or nearby village. I like to use settings from real life, but some people use settings from video games, or even invent settings from pure imagination. If you ever run out of settings, go and explore a new town, or play a new video game!

Settings can be large or small. The more familiar you are with a setting, the more precise each location within it can be, and so the more locations you can fit inside. For example, if you are a gardener and have a keen knowledge of every plant in your garden, then each plant can be its own location in the setting of your garden. If your plants are arranged in a way that creates clear sequences of locations (and you don’t change them too often), this would make a great memory palace. However, if you have only a vague sense of the plants in your garden or local park, then they are not distinct locations in your mind, so you will not be able to fit as many locations in the space. You can use larger features, such as “the flowerbed”, “the pond”, or “the bird bath” as locations instead.

Mapping the locations

You have a tree diagram, and you have a setting. It’s time to put them together. This means creating paths through your setting: sequences of locations, with branches in the path to match the structure of the tree diagram. For example, if your tree diagram has a sequence of three move pairs before dividing into two options, then you can create a path through your memory palace of three locations in a row, before you get to a natural junction where you split into two paths going in different directions.

Mapping locations is quite easy to do, but it is difficult to do well. If you want to memorise a burner repertoire for a single game this afternoon, then you don’t need to worry too much: just create paths wherever convenient and get memorising. But if you want to memorise a repertoire for the long term, then it’s worth doing this process carefully, to make your memory palace as intuitive as possible.

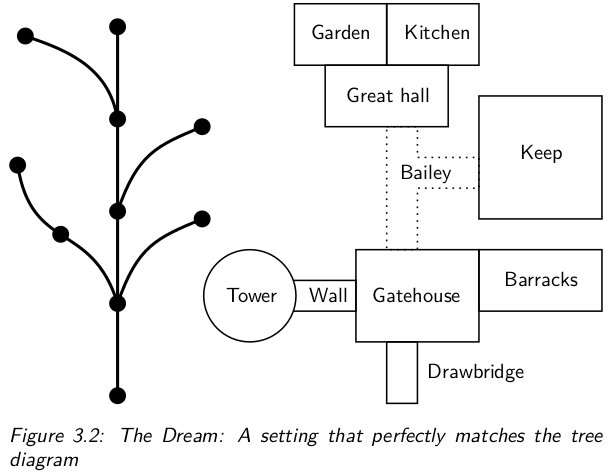

What do I mean? Ideally, your setting would perfectly match your tree diagram (like Figure 3.2). Your first location, the root of your tree, will be at at an obvious entrance to the setting, like the drawbridge of a castle. The second location would be in the gatehouse. Wherever your tree diagram branches, there would be a corresponding branching point (junction) in your setting. After the second location, your tree diagram branches into three options, which conveniently matches three routes in your setting: left along the wall, forward into the courtyard, or right into the barracks…

Of course, it is very unlikely you can find a real life setting that fits your tree diagram perfectly. Sometimes you will need to create paths in strange places, like hugging the outside of a building, or digging through a wall to an imaginary tunnel beyond. But if you take care to consider the overall shape of the repertoire, you will be surprised how many “lucky coincidences” turn up to create a close fit.

I find the best way is to start by allocating areas of my tree diagram to different areas of my setting, then later going back to plot each location precisely. For example, when first mapping the Spanish Exchange Airport repertoire (Chapter 5), I allocated the small branching segment to the aeroplane in general, as I was confident that I could fit six locations in a plane. Then later I went back to assign each of the six move pairs a precise location within the plane – the entrance, the cockpit and so on. Figure 3.3 shows an interim stage; we already saw Figure 2.3 which is a map of the locations, and Figure 2.2 which is the tree diagram labelled with locations and picture words, ready to memorise.

Keep your paths as simple as possible. Imagine you are playing this repertoire in a tournament game, one year from now. Will you still remember where the paths go? If they branch at obvious points, like a hallway, you should be okay. If they are convoluted and pass from the door to the window and back to the door, you are in trouble. It is better to miss out a promising location than to backtrack. And never let your paths cross!

Remember also that you might want to add to your repertoire in future. Perhaps you will want to extend a variation for a few more moves, or add a new variation early on. This will be harder if your memory palace is cramped and already uses every last space.

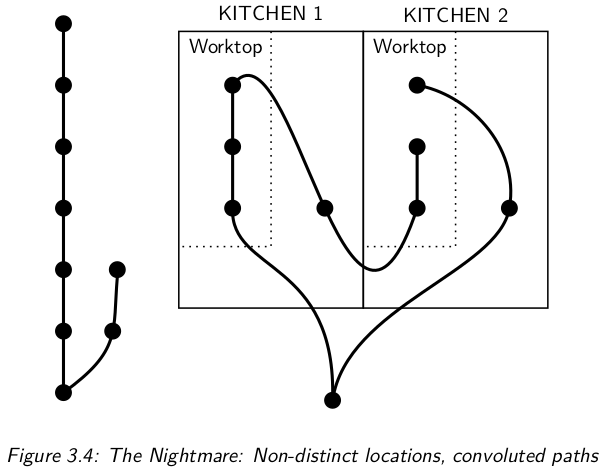

Each location must be distinct. In my office, I have eight locations on the kitchen worktop: fridge, sink, water cooler, and so on. But I can’t then walk up to the floor above and map eight more locations onto their kitchen worktop, because it looks the same. When I think “office fridge”, I want exactly one composite image to come to mind. If I try to store two composite images in two similar office fridges, then either the images will get mixed up, or one image will wipe out the other in my memory. (Figure 3.4 is an illustration of what not to do.) As you practise using memory palaces, you will get a feel for which locations you can distinguish, and which you will get confused.

Finally, my last tip is to not get stuck in analysis paralysis! The only way to learn is to start. You will have to make many arbitrary decisions about paths and locations. If you find one of your paths at a dead end, you can always float through walls, shrink yourself to a tiny size and explore ten mini locations on your desk, or create a portal to a completely different place. Just try to avoid doing this too much; your memorising and recall effort should be focused on your picture words, not the palace.2

When you have finished mapping your tree diagram to your setting, try navigating around it. Can you follow your paths without confusion? Can you identify every location? Once you are happy with your empty memory palace, label your tree diagram with the names of every location, or write it out neatly from scratch, like Figures 4.4 and 5.6.

Your memory palace is still a quiet and lonely place. Let’s choose picture words to put in it.

Selecting picture words

Algebraic notation and picture notation have a one-to-many relationship. This means that in a chess position, a valid picture word will represent exactly one chess move, but one chess move can be represented by several picture words. Figure 3.5 shows a few examples. When you design your composite images at home, you need to decide which picture word to use.

Let’s suppose you want to memorise a repertoire in the Bayonet Attack against the King’s Indian Defence. You are learning the repertoire from White’s perspective, so each picture word pair will show Black’s move followed by your reply.

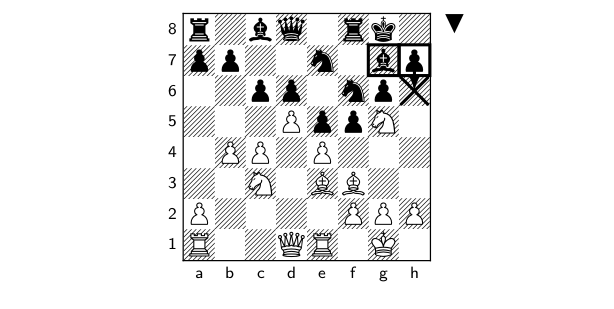

In the position below, Black’s most common move is 13...h6.

13...h6 is a move to h6 by candidate piece II so, referring to the Appendix, your picture word options are (Bobby) Fischer, fishcake, or (Mount) Fuji. All three are valid picture words for 13...h6.

Using the techniques of Chapter 2, you should be able to turn any of these into a memorable image. But which will be easiest? Choose a picture word that (a) is easy to imagine interacting with other picture words, and (b) already has strong associations for you.

Of the three options, Fischer is the most interactive. It is easy to imagine him as the first (active) picture word in a pair, eating or kicking or hugging the second picture word. It is also easy to imagine him as the second (passive) picture word, reacting to whatever has happened.

However, I don’t have strong associations with Fischer in my mind. (This might be different for you.) Although I have admired his games, I don’t have a clear impression of what Fischer looked or sounded like. I could watch a video but, unless he was particularly distinctive or I have a continued interest, this is unlikely to help for long. So it will be hard for me to keep Fischer clear in my memory.

Fishcake is the opposite. I have strong associations because I have eaten many fishcakes, so I know how they look, taste, and smell. However a fishcake is not very interactive. It would be fine as the second (passive) picture word in a pair, letting out a gooey mess of fish and sauce as it gets eaten, but it is hard to imagine a fishcake taking action as the first picture word.

So for me, the best picture word is Mount Fuji. I have fairly strong associations with Mount Fuji, from the painting The Great Wave off Kanagawa, and once seeing its lower slopes from a hike. With a bit of imagination, it is not hard to visualise it taking action by erupting or causing an avalanche on someone. If it is the second picture word in a pair, I can imagine it letting out a puff of smoke as it gets hit (or otherwise affected) by the first picture word. I can also easily imagine it interacting with its location, for example if I had Mount Fuji in a yacht, I could imagine its slopes twisting and bending the wooden deck below, and its eruption burning the sails above.

To repeat, with enough creativity, I could use any of the three options as my two-syllable picture word for h6. But the question was, which is easiest? For me, the answer is Fuji. For you, the answer may be different. It depends which picture word you find most natural to animate, and it particularly depends on the associations you already have in your mind.

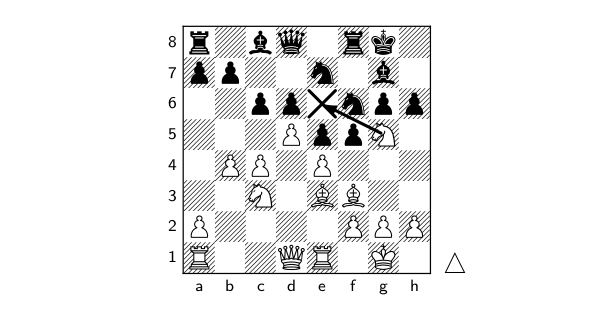

You plan to meet 13...h6 with 14.Ne6. Referring to the Appendix, the one-syllable options for e6 are leech, bleach, sledge,3 and slush.

For me, leech is clearly the best of these picture words. I already have strong associations with leeches, from my natural reaction to the idea of leeches sucking blood, and reading about their historical use in medicine. And although I have never held a leech, I am familiar with slugs, which are similar. It is easy to imagine leeches interacting with other picture words, either actively – by sucking their blood, of course – or passively – by being squished.

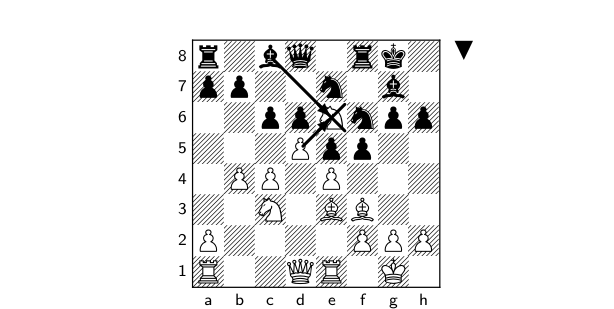

The next two moves are 14...Bxe6 and 15.dxe6, which both take one-syllable picture words.

I have already chosen my one-syllable picture word for e6: leech. So I must stick to it! This picture word pair will be “a leech sucking another leech’s blood”. Not pleasant, but memorable.

Don’t be tempted to add variety and memorise this as “bleach pouring over slush” or suchlike. Be consistent with your choices. As you practise memorising your favourite picture words in different situations, you will grow familiar with them, like recurring characters in a play. You will learn how to visualise them in clearer and more exaggerated ways, which will make your memories more distinct. This will also make it faster to visualise your composite images at home and to decode the images back into chess moves at the board.

It is particularly tempting to change your picture word when the location in your memory palace fits one of the alternative options. If you were memorising this repertoire in a supermarket, and you came to the cleaning products aisle, it might be tempting to say “I normally visualise e6 as a leech, but here bleach fits better”. This looks sensible but is actually a terrible mistake: as time passes, the bottle of bleach will fade into the background, and you won’t be able to to recall it as a picture word.

Finally, as with locations, you should make sure your picture words are all distinctive. If you use a leech for e6, you should not use a slug for e7. They are too similar.

Again, this depends on your associations: if you are a herpetologist, it is fine to use both frog (h4) and toad (a1) in your memory palaces, but the rest of us should choose just one or the other. Personally, I use frog for h4 and toast for a1 – although toad is a more natural picture word than toast, the similarity with frog is too great. Whenever I saw a green, hopping amphibian in my memory palaces, I wouldn’t know if I were looking at a frog or a toad.

If you do have two similar picture words, it is not the end of the world. Just visualise them, consistently, in different ways. I use both tulip for a5 and lily for e5. My tulip is a motherly flower who likes to hug with her leaves. My lily is a water lily who tends to wrap around things like a rope.

The first time you convert a repertoire into picture notation, it will be quite time consuming to decide on your picture words. As you build more memory palaces, this will be quicker, because you will have made most of the choices already.

Memorising the palace

Now you have given every move pair a location and two picture words, just as Figure 2.1 requires. You are almost ready to begin memorising – but first it is wise to double check your paths and picture words against your repertoire. Memory techniques are so effective that if you memorise something in error, it is annoyingly difficult to forget it again. Then when you are satisfied, it is time to begin memorising!

You already know how to do this step, from Chapter 2. Take each location in turn, introduce the two picture words, and make them interact with each other and the location in funny, grotesque, and dramatic ways. Have fun!

-

I will not cover how to create a repertoire. Refer to any opening book. ↩

-

If you do need to use a portal, you need a way to remember where the portal leads. The destination location should bleed through the portal to interact with the current location. For example, I once got stuck in a university building and needed to portal out to a river nearby. I created a portal in the building, with the river spilling through the portal into my current room. ↩

-

Which can also be pronounced sled, another reason not to recommend it. ↩

Watch on YouTube

Watch on YouTube