Chapter 1 - Picture Notation

You are reading an online version of The Chess Memory Palace by John Holden.

Copyright © 2022 John Holden, all rights reserved.

Click here to return to the online contents page.

For the best reading experience, you can buy

the paperback or

the ebook.

Subscribe to

@ChessMemoryPalace on YouTube

for video tutorials.

You are reading an online version of The Chess Memory Palace by John Holden.

Copyright © 2022 John Holden, all rights reserved.

Click here to return to the online contents page.

For the best reading experience, you can buy

the paperback or

the ebook.

Subscribe to

@ChessMemoryPalace on YouTube

for video tutorials.

Amazon links are affiliate links — this gives me a little bit more for each sale, at no cost to you. I earn from qualifying purchases.

Note October 2025: If you find Picture Notation difficult, you may prefer Image Notation. This follows algebraic notation more closely. The rest of the book (how to memorise composite images, how to build a branching memory palace etc) applies as before.

I know from my own experience what an excruciating labour it is to memorise “theory” before a game. You have it all written down in notebooks, you have gone through it ten times before starting play, and still you can’t remember it.

IM and Chess Trainer Mark Dvoretsky

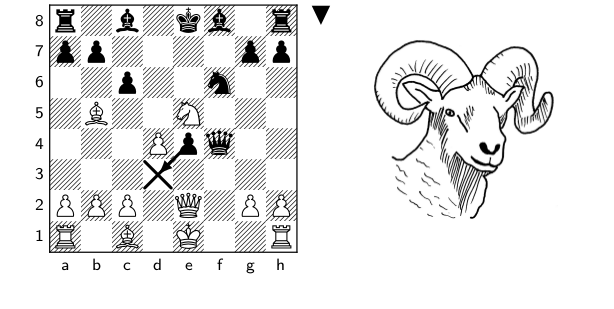

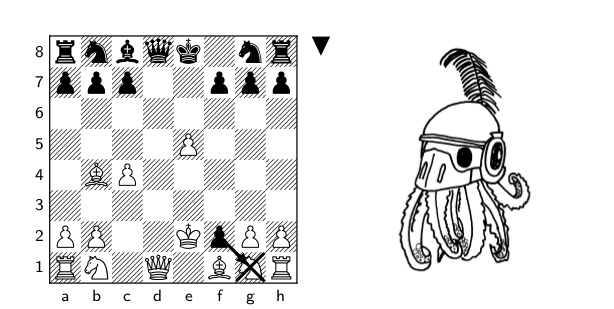

Algebraic notation is the most popular way to write chess moves. But it is not the only way. In the position below, a variation of the Schliemann Defence to the Ruy Lopez, Black now captures the pawn on f4 with the Queen.

Black’s move can be written “Qxf4” (algebraic notation), “Qg5xf4” (long algebraic notation), “g5f4” (Smith notation, commonly used by computers), or “7564” (International Correspondence Chess Federation numeric notation), among other systems.

These notations have two things in common: they all identify the target square (f4 or 64) and identify which piece moves to that target square (Q, or the piece on g5/75).

This chapter introduces picture notation, which works on the same principle. Each move is represented by a picture word (for example shark), where the first two relevant consonant sounds (sh, r) identify the target square, and the number of syllables (one) identifies the candidate piece that moves.

Picture notation is useful because pictures are easy to memorise using the techniques in Chapter 2.

Target squares

The first two relevant consonant sounds of each picture word identify the target square.

The first two consonant sounds in shark are sh and r, which identify the target square f4 using the system below. Each file/rank has a set of consonant sounds, and for each I have written a short memory aid.

-

d, t, th. The letter t has one downstroke.

-

n. The letter n has two downstrokes.

-

m. The letter m has three downstrokes.

-

r. The word four ends in an r.

-

l. “Five alive."

-

ch, j, tch, sh. Think of the “soft" curvy shape of the digit 6 and the “soft” sounds of sh and j .

-

hard c, g, k, ng1, q. Think of the “hard" angular shape of the digit 7 and these “hard" sounds.

-

f, ph, v. A calligraphic f looks like an 8.

We ignore the consonant sounds s, z, and soft c; b and p; and also h, w, and y. We also ignore vowels.

The picture word shark identifies f4 because sh, the first consonant sound, identifies the f-file; and r, the second consonant sound, identifies rank 4. Ignore any further consonant sounds (k).

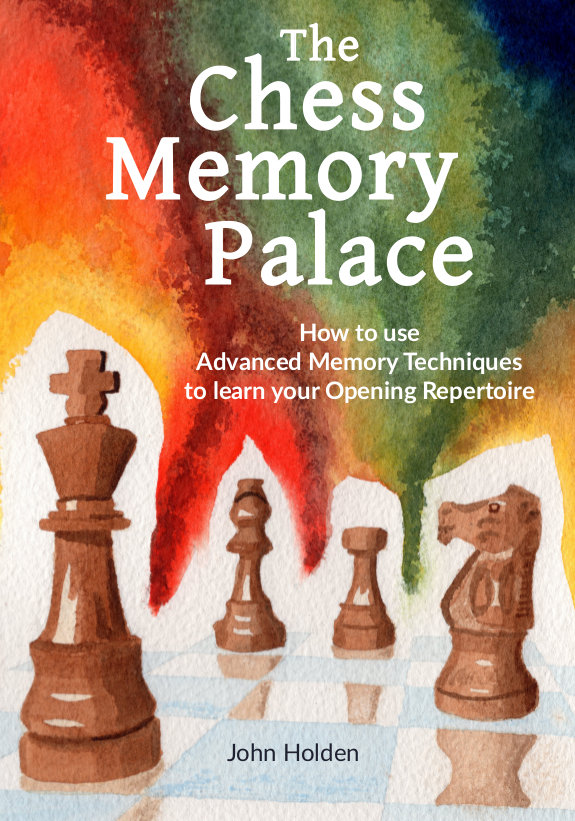

The picture word brush identifies d6. The b is ignored; r identifies the d-file; and sh identifies rank 6.

Why is shark f4 and brush d6? Because of the order of the consonant sounds. sh then r is the 6th file followed by the 4th rank: f4. r then sh is the 4th file followed by the 6th rank: d6. The first consonant sound (ignoring consonant sounds such as b that have no meaning) is always the file, the second consonant sound is always the rank. Similarly, mole (m then l) is c5, while lamb (l then m) is e3.

The picture word airship also identifies d6. The first consonant sound, r, identifies the d-file. The second consonant sound, sh, identifies rank 6. We have already used the first two consonant sounds to identify d6, so we ignore the rest of the word.

Because brush has one syllable and airship has two syllables, these picture words represent different pieces that move to the target square d6 – more on this later.

Practice: Finding the target square

You are playing the White pieces, and your opponent has surprised you by responding to your trusty Ruy Lopez with the Schliemann Defence, hoping you will slip up in the opening. It has been a long time since you last faced this sharp line, but happily you stored your preparation in a memory palace a few years ago (Chapter 4) and have kept the memories sharp with spaced repetition ever since (Chapter 7).

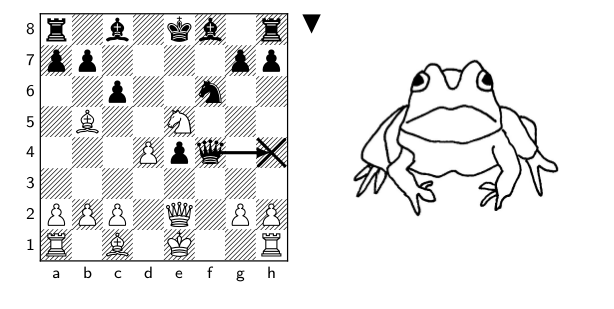

You reach 9...Qxf4. Time to wander through your memory palace…

You discover a shark biting a jester (lol2); a match catching fire and burning a lion’s nose, making the lion roar; and a frog chewing gum.

As an experienced user of the chess memory palace, you immediately recognise six picture words, in three pairs: shark and lol, match and roar, frog and gum. (For those who like to read ahead, we are following Figure 4.5.)

Your opponent has just played 9...Qxf4 (shark). You must respond lol. The consonant sounds are l and l, identifying the e-file and rank 5: e5.

Only one piece can move to e5, so you pick up the knight from c6 and play Ne5. Discovered check.

You expect your opponent to play match. M and tch are the consonant sounds, identifying the c-file and rank 6: the target square is c6.

As expected your opponent pushes the c7 pawn to c6 to block the check and threaten your bishop.

Move 11 is a sharp position with only one good move. Fortunately you don’t have to calculate: you remember the match burning a lion’s nose and making it roar. Roar. Two r sounds: the d-file and rank 4, must mean the target square is d4.

Only the pawn on d2 can move to d4. So you play 11.d4 and hit the clock.

Now you have reached a frog chewing gum in your memory palace. While you visualise the memory, your opponent sweeps her queen to h4 with check. Is that what you expected? You expected frog, consonant sounds f and r. F identities the h-file and r identifies rank 4, so yes 11...Qh4+ is what you expected.

Your memory palace shows the frog chewing gum. G is the g-file and m, with its three downstrokes, is rank 3. The target square is g3.

Only the g2 pawn can move to g3, so you push it one square forward and await your opponent’s next move…

Captures and checks

As we have seen, there is no special notation for a capture in picture notation. Shark indicates a piece moving to f4, whether or not there was an enemy pawn on that square. Both ...Qf4 and ...Qxf4 would be written shark.

There is also no special notation for a check. Frog identified ...Qh4+, but would have identified ...Qh4 just the same if there were a white pawn on f2 and no check.

Checkmate and stalemate have no special notation either.

Candidate pieces

What if more than one piece can legally move to the target square? We decide which candidate piece to move using the number of syllables in the picture word. I will explain the theory, and then we will see it in practice.

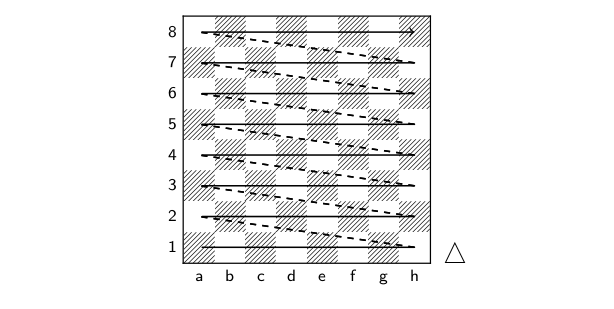

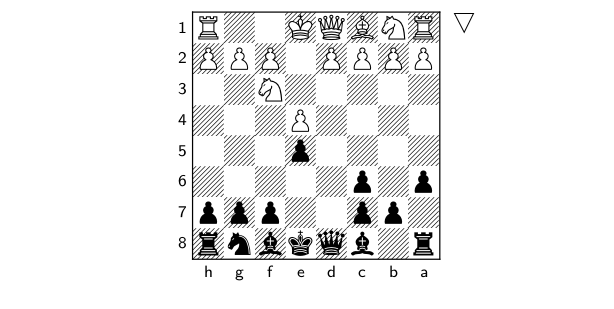

First, list every piece that can legally move to the target square (ignoring castling). Starting from the back rank, label them I, II, III, IV…3 When White is to move, the bank rank is rank 1. When Black is to move, the back rank is rank 8.

If more than one candidate piece is on the same rank, give the lower number to the piece closest to the a-file – White’s left, Black’s right. In other words, if more than one candidate piece is on the same rank, give the lower number to the piece standing on the file that is earlier in the alphabet.

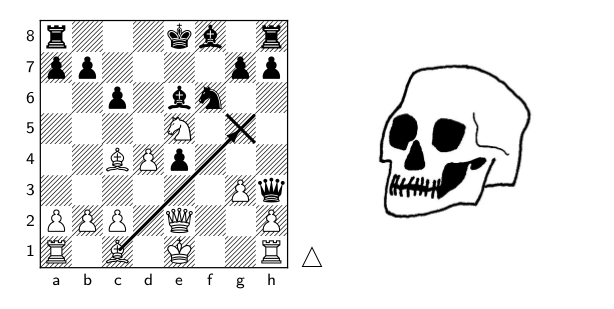

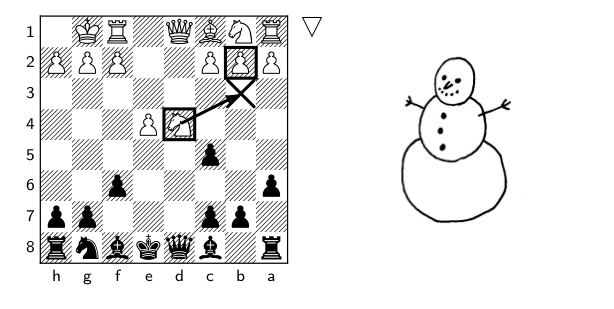

So, with White to move, the candidate pieces are in order on the following arrow:

With Black to move, the back rank is rank 8, so the candidate pieces are in order on a different arrow:

Second, after you have labelled all the candidate pieces, count the number of syllables in the picture word. Third, pick up the candidate piece with the matching number and move it to the target square.

If the picture word has one syllable, for example roar, move candidate piece I. If it has two syllables, for example robber, move candidate piece II. If it has three syllables, for example warrior, move candidate piece III. If it has four syllables, for example barbarian, move candidate piece IV.

Let’s see this in action.

Practice: Choosing the candidate piece

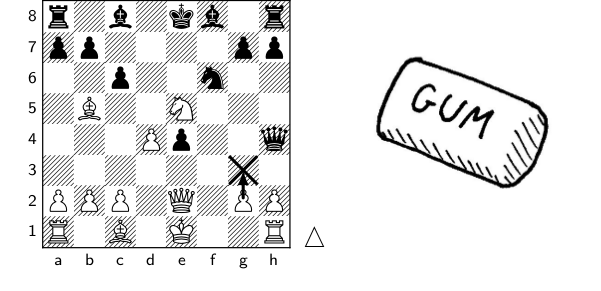

After watching the frog chewing gum, you continue walking along your memory palace to discover your next pair of picture words: a vampire biting a samurai.

You are expecting your opponent, Black, to play vampire. Vampire of course identifies the target square h3: the first consonant sound v identifies the h-file, and the second consonant sound m identifies rank 3.

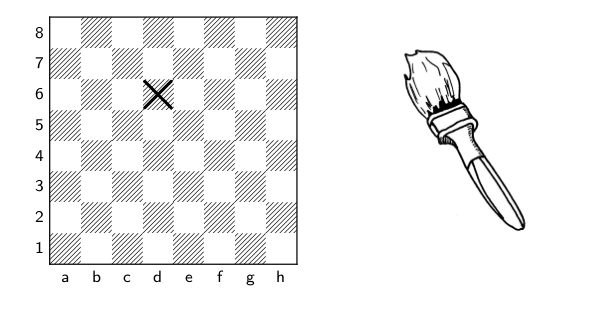

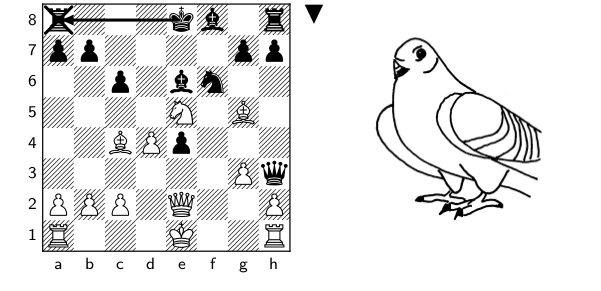

But two pieces can move to h3: the bishop on c8 and the queen on h4. Which piece does vampire identify?

In this case, Black to move, the bishop is on your opponent’s back rank, so it is piece I. The queen is more advanced, so it is piece II. Vampire has two syllables. Your opponent picks up the queen, correctly, and moves it to h3, little knowing what is going on inside your head.

Your prepared reply is samurai. Ignoring the s as always, the first two consonant sounds are m and r, identifying the target square c4.

Four pieces can legally move to c4: the pawn on c2, the queen on e2, the bishop on b5 and the knight on e5. The pawn and queen are the furthest back, on the second rank, and the pawn is closer to the a-file than the queen. Therefore the pawn is candidate piece I and the queen is candidate piece II.

The bishop and knight are further advanced, on the fifth rank. The bishop is closer to the a-file than the knight. Therefore the bishop is candidate piece III and the knight is candidate piece IV.

In this position, the picture word Mir, one syllable, would identify c2-c4 with the pawn. Meerkat, two syllables, would be Qc4. Marionette, four syllables, would be Nc4.

But your picture word is samurai. Three syllables. So you pick up candidate piece III, the bishop, and retreat it out of harm’s way to c4.

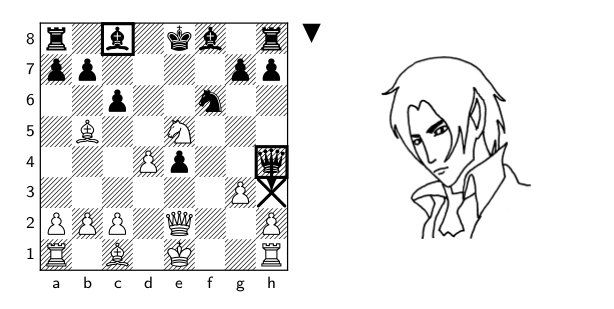

While your opponent ponders her next move, you walk on in your memory palace to find a rather horrible scene of a leech sucking a skull.

So your opponent should play leech: something to e6.

Again, the light-squared bishop and the queen can legally move to the target square. The bishop, on the back rank, is piece I. The queen is more advanced, so is piece II. (You don’t need to ask which piece is closer to the a-file. That’s only to break ties when two candidate pieces share the same rank.) Leech has one syllable, so your opponent should move the bishop, piece I, to e6. (...Qe6 would have been polish, two syllables.) As expected, your opponent plays ...Be6.

What was the leech sucking? A skull. So you should reply with a move to the target square g5.

Only the bishop on c1 can move to g5, so you don’t need to count syllables. You pick up the bishop and confidently play 14.Bg5.

Castling

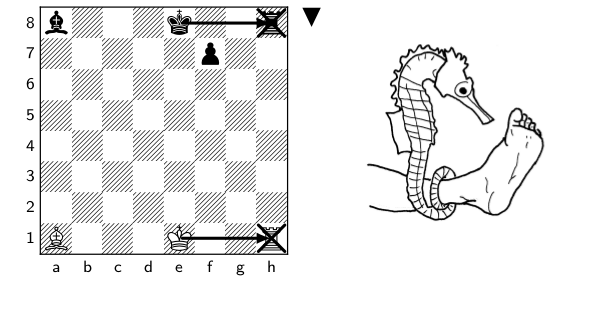

Picture notation identifies castling using the one-syllable picture words for a1, h1, a8 or h8.

On White’s move, if White can legally castle queenside, toast (a1) identifies O-O-O. If White can legally castle kingside, foot (h1) identifies O-O.

On Black’s move, if Black can legally castle queenside, dove (a8) identifies ...O-O-O. If Black can legally castle kingside, five (h8) identifies ...O-O.

On some chess software and websites, users can castle by dragging the king onto the rook. This is the same principle.

Let’s get back to the Schliemann game!

Practice: Castling

You are happy to move on from the leech sucking the skull, and walk through your memory palace to the next pair of picture words: a dove munching toast.

So your opponent should play dove.

Dove identifies the target square a8, which is currently occupied by a black rook, so this must mean 14...O-O-O. Sure enough your opponent castles queenside and hits the clock.

Your prepared response is toast: the target square a1.

This can’t be a move to a1, because a white rook is sitting there already, so you play 15.O-O-O.

Note that on White’s turn, maid – one syllable – would have identified Rc1, and swimsuit – two syllables – would have identified the retreat Bc1, not O-O-O. Castling is always identified by toast, foot, dove or five.

En passant

En passant is an immediate pawn capture on the square behind a pawn that has just advanced two squares. In picture notation this is simply notated as a move to the target square by the capturing pawn. There is no special notation for en passant.

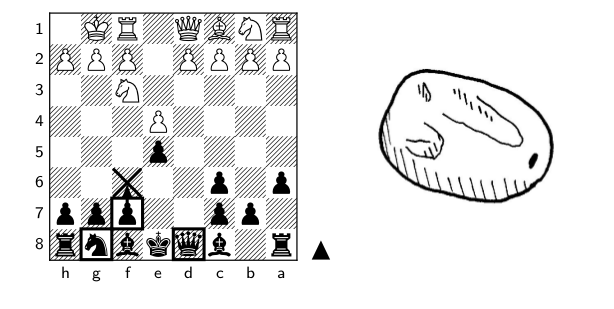

For example, in the position below White has just played roar (11.d2-d4). Theory is for Black to respond frog (11...Qh4+). However Black could legally play the blunder ram instead (11...exd3 en passant).

The candidate piece and syllable rules apply as normal. In the Opocensky Variation of the Najdorf Sicilian, White targets the hole on b6. If Black tries to break with ...b7-b5, in one variation we reach the position below.

Only the e3 bishop and a5 pawn (by capturing en passant) can legally move to b6. The bishop is further back, so the bishop is candidate piece I and the pawn is candidate piece II. Sponge, one syllable, identifies Bb6. Banjo, two syllables, identifies axb6 en passant. White should play banjo.

Picture word pairs

By now you will have noticed that I often introduce picture words in pairs. This is because chess moves come in pairs: “If Black plays shark, I will reply lol." Conveniently, this also makes the picture words easier to remember (Chapter 2).

When combining two picture words into a pair, it is important to get the order right. The first picture word should do an action to the second picture word, or use the second picture word as a tool. In other words, the first picture word is more active, the second picture word more passive. The first picture word should also be physically higher in the scene. See Figure 1.1.

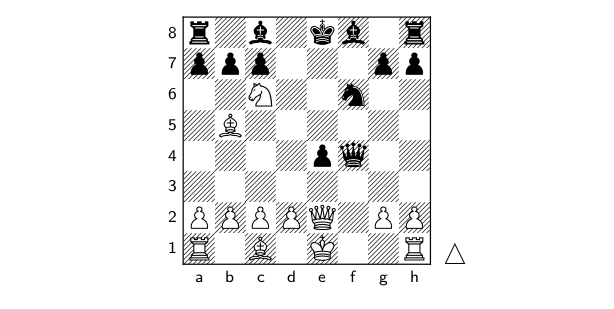

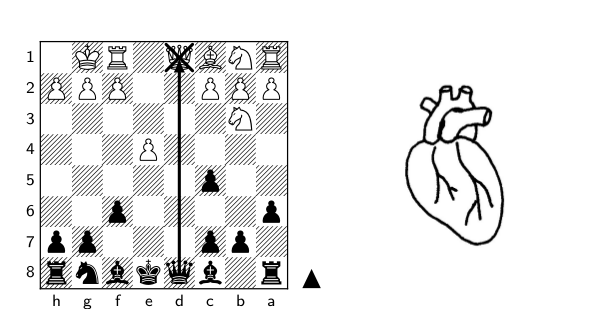

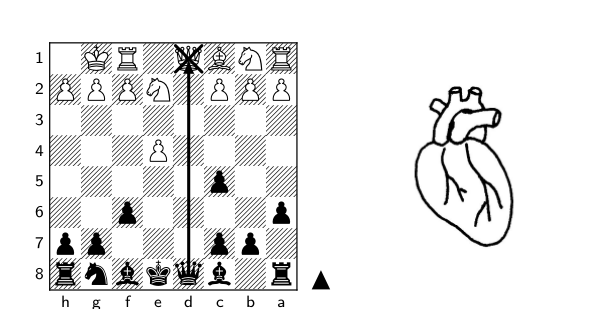

In the position below, with Black to move, we have seen that theory is “leech sucking a skull".

Leech (...Be6) comes first because the leech is doing the action to the skull, and on top of it. The opposite order would be “skull eating a leech", or perhaps “skull crushing a leech". This would identify Black playing ...g5 followed by White’s Be6, which doesn’t make any chess sense.

Let’s see another example. In the position below, Black to move, “a seahorse (shaped like the digit 5: the picture word five) hooking a foot" represents Black castling kingside followed by White castling kingside. Five (h8) comes first, then foot (h1).

If instead we had “a foot kicking a seahorse (five)", then foot (h1) comes first, followed by five (h8). So the moves are ...Bxh1 and then Bxh8. (Not ...Rxh1, because foot has one syllable, and the bishop is candidate piece I.)

There are three points worth special attention.

First, although White castling kingside is always represented by foot, and Black castling kingside is always represented by five, foot and five do not always represent castling. The meaning of picture notation depends on the board position.

Second, if a picture word pair contains two of the same picture word, you don’t need to worry about role (active versus passive) and position (higher versus lower), because the order is reversible. For example, an exchange on d4 might be represented by the picture words roar roar. “Two lions roaring at each other" is a good image for roar roar.

Third, the best picture words are concrete nouns, easy to visualise and play with in your imagination. (We will discuss this in detail in Chapter 3.) So from now on, we will always represent the picture word roar (d4) as a lion. A lion is simpler and easier to visualise than the action of roaring. Whenever you see a lion in your memory palaces, it always represents roar (d4), never e2.4

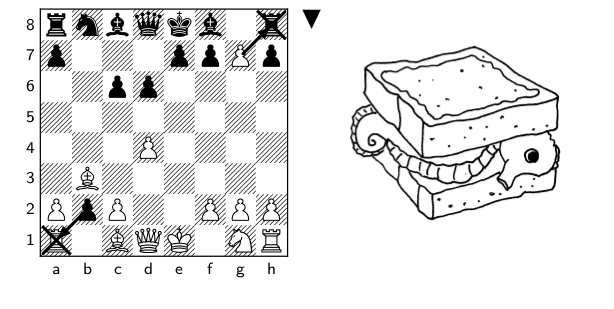

Promotion to a queen

Promotion is very rare in opening theory, so you can safely skip these next two sections. But, for completeness, this is how you show promotions in picture notation:

A pawn promotion to a queen is just a pawn move to the furthest rank. There is no special notation for a promotion to a queen. The queen is assumed.

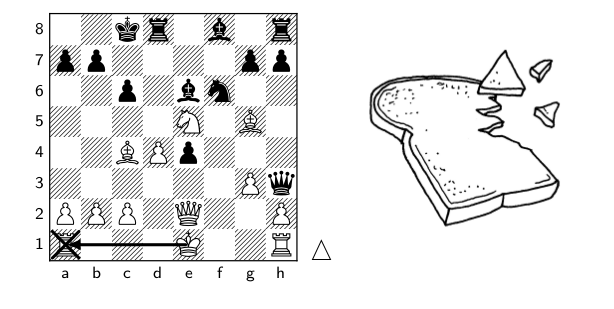

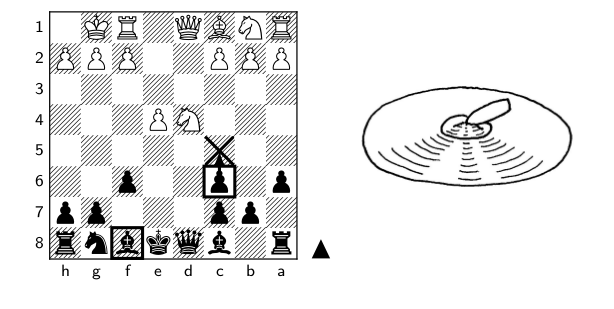

Early promotions occur in a variation of the Czech Defence, which happens occasionally in amateur games. The diagram below follows 1.e4 d6 2.d4 Nf6 3.Nc3 c6 4.Bc4 b5 5.Bb3 b4 6.e5 bxc3 7.exf6 cxb2 8.fxg7.

Black to move plays toast (8...bxa1=Q). White then replies five (9.gxh8=Q).

For the picture word pair toast five, I imagine a “seahorse sandwich”: the top piece of toast is above, and in a sense doing an action to, the seahorse. (Five toast would be “a seahorse eating toast”, of course.)

The resulting position has four queens on the board.

Underpromotion

With underpromotion, we have to add an extra element to the picture word.

-

If the pawn promotes to a rook, add a chess rook or a strong tower (or a corvid bird “rook”).

-

If the pawn promotes to a bishop, add a bishop.

-

If the pawn promotes to a knight, add a knight or a war horse.

So, in the Czech variation above, if Black played 8...bxa1=R, the picture notation would be toast (with a rook). Imagine a slice of toast with a chess rook punching through it. If White played 9.gxh8=B, the picture notation would be five (with a bishop). Imagine a seahorse (in the shape of the digit 5) blowing bubbles at a bishop.

Underpromotion to a knight features in the Lasker Trap of the Albin Countergambit. The diagram below follows 1.d4 d5 2.c4 e5 3.dxe5 d4 4.e3 Bb4+ 5.Bd2 dxe3 6.Bxb4 exf2+ 7.Ke2.

Black gains a crushing advantage with squid (with a knight) (7...fxg1=N+). I would imagine a squid wearing a knight’s helmet.

White has played badly but Black’s moves have been good (given the opening), so this could plausibly feature in a memory palace. This line has been seen thousands of times in online play.

We normally memorise picture words in pairs. When there is an underpromotion, we need three elements instead of the normal two: the two picture words, plus the rook or bishop or knight.

But you will probably never need to memorise an underpromotion, so forget about it. Refer back here if you ever need to.

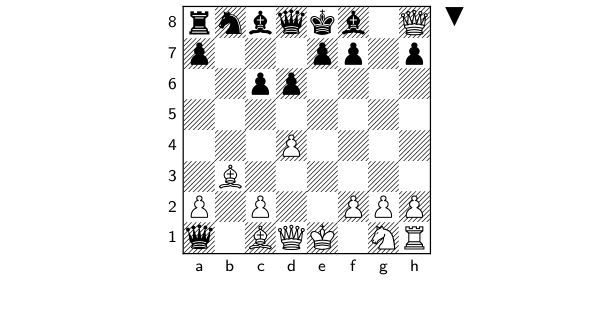

Your turn

Now you have learnt picture notation! I encourage you to try it for yourself.

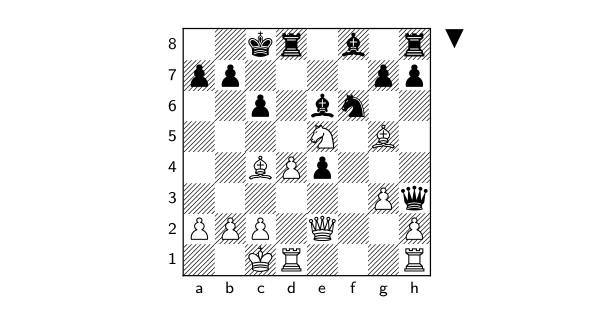

This time you are playing the Black side of a Ruy Lopez Exchange, when you reach the following position with your opponent, White, to move.

I am showing the diagrams from Black’s point of view because that is how you will experience it at the board.

The next three picture word pairs in your memory palace (from Figure 5.7) are:

-

A monopod (foot) kicking a jujube fruit

-

A lion (roar) pounces on a robber

-

A robber hits a cymbal5

Because you memorised this memory palace from Black’s perspective, each picture word pair shows White’s move followed by Black’s reply. The first picture word (active, higher) is White’s move, the second picture word (passive, lower) is Black’s reply.

Now the path you are following through your memory palace branches, indicating two possible moves for your opponent, and your response to each.

-

A snowman pulls a beating heart out of its snowy chest

-

Or, a balloon pops to reveal a beating heart inside

Starting with “foot kicking a jujube fruit", play out these moves on a board, then check the answers below.

Answers

Foot identifies the target square h1, because the first consonant sound f identifies the h-file, and the second consonant sound t identifies rank 1. There is already a rook on h1, so foot in this position means O-O.

I have drawn foot as the mythical “monopod" creature, because this will be convenient in Chapter 2 when we memorise the images.

Black plays jujube. The j sounds identify the f-file and rank 6: the target square f6. Three candidate pieces can move to f6: the queen, the g8 knight, and the f7 pawn. The queen and knight are on the back rank, so they must be candidate pieces I and II. The queen is closer to the a-file. Therefore the queen is candidate piece I, the knight is candidate piece II, and the f7 pawn – on a more advanced rank – is candidate piece III. Jujube has three syllables, so the move is ...f7-f6.

Your opponent, White, should play roar, which we have already seen identifies the target square d4. The d2 pawn, on rank 2, is candidate piece I. The f3 knight, on the more advanced rank, is candidate piece II. Roar has one syllable. So the move is 6.d4.

You play robber. This also identifies d4: the consonant sound b is ignored, so the two consonant sounds are r and r. The queen on d8, on the back rank, is candidate piece I, and the more advanced pawn on e5 is candidate piece II. Robber has two syllables. Therefore as Black you pick up the e5 pawn and capture on d4: 6...exd4.

Your opponent can now play robber as well. As we have seen, this is d4, two syllables. The two candidate pieces that can move to d4 are the queen on d1 (candidate piece I) and the knight on f3 (candidate piece II). As expected, your opponent plays 7.Nxd4.6

Your planned response to robber is cymbal. The soft c and b sounds have no meaning, so the two consonant sounds are m and l: c5. Two pieces can move to c5: the bishop on f8 and the pawn on c6. The bishop is on the back rank, so is candidate piece I, while the pawn, further advanced, is candidate piece II. (Remember, we do not ask which piece is closer to the a-file except to break the tie when two candidate pieces share the same rank.) Cymbal has two syllables so you confidently pick up piece II, the pawn, and play 7...c5.

At this point, your memory palace splits into two paths. While your opponent ponders her move, you explore both paths of your memory palace, to recall the picture word pairs snowman heart and balloon heart. So your opponent can play snowman or balloon, and either way you will reply heart.

Your opponent chooses to retreat the threatened knight to b3: 8.Nb3. This matches the two-syllable picture word snowman: the first two relevant consonant sounds are n and m: b3. The pawn on b2 is candidate piece I, while the more advanced knight on d4 is candidate piece II.

In response to snowman, you prepared heart. H is ignored, r identifies the d-file, and t identifies rank 1. So you must move to d1. Only the queen on d8 can move to d1, so you quickly play 8...Qxd1.

Alternatively, your opponent could have played balloon. B is always ignored, so the first two consonant sounds are l and n, identifying the target square e2, with two syllables. The queen on d1 is candidate piece I, and the knight on d4 is candidate piece II, so White’s move in this variation is 8.Ne2.

Black’s response is still heart, which again means d1 with the only piece that can move there, the queen: 8...Qxd1.

Moving on

In this chapter, we have discussed picture notation in one direction: converting a picture word (shark) into a chess move (...Qxf4). You need to do this in your head, at the board. If you would like more practice, there are four complete games with algebraic and picture notation side by side in Chapter 7.

You do not need to convert chess moves into picture notation in your head. You can do this at leisure sitting at home, with full use of the Appendix, where I have listed picture words for all 64 squares.

But we are getting ahead of ourselves. We will start designing memory palaces in Chapter 3. First we need to learn how to memorise the picture words, using the powerful techniques of memory competitors. On to Chapter 2!

-

When pronounced as an sound, like the ng in hummingbird. ↩

-

The online shorthand for laugh out loud. Whenever you see a jester in your memory palaces, the picture word is lol (e5, one syllable). ↩

-

I use Roman numerals to avoid confusion with files and ranks. ↩

-

I recommend plane as the one-syllable picture word for e2. Imagine a toy plane flying around. ↩

-

The cy sounds like an s, so we ignore it. Apologies to non-native English speakers. You will quickly get used to the English picture words that feature in your memory palaces. ↩

-

Roar (7.Qxd4) is possible too: see Figure 5.7. ↩

Watch on YouTube

Watch on YouTube