Why memorise chess opening theory (with a memory palace)?

I’ve done the analysis with my engine, and I’ve organised everything, and I understand it and I get it – I just can’t remember it.

GM Patrick Wolff1

Last year I published The Chess Memory Palace, a guide to using memory techniques to memorise a chess opening repertoire.

I have read some discussion doubting whether it is useful for a chess player to memorise moves. For the most part, I am not too worried by this question. I am content to say that if you want to memorise a chess opening repertoire, this is the way to do it. If you don’t, then this is not the book for you.

But I am also a bit surprised by the question. It seems to be a fact that both professionals and amateurs do, in fact, spend significant time memorising moves, yet often complain of forgetting. And I know from my own club-level experience that I get better results (and enjoy the game more) when I recall my opening prep and enter the middlegame I wanted.

The way I try to briefly deal with this question in the intro is to ask, would it help to write down your repertoire on paper and take it with you to a game? You would still have to understand your moves and study the middlegame plans, of course, but your written-down moves will help remind you of your plans. (There is probably a link here to the role of memory in learning, in general, where plain memorisation of facts can help later understanding.) Bringing notes to a chess game certainly wouldn’t make you a worse player – in fact, you’d be banned for cheating! Using a memory palace is like reading your repertoire while at the board. I am not claiming more than that. But I am also not claiming less than that.

There is a legitimate debate to be had about study time trade-offs. Imagine that, to maintain your opening repertoire memory, you would need to spend 1 hour a month rehearsing your memory palaces, versus 10 hours a month drilling flashcards. If the flashcards gave you enough transferable chess knowledge, it might still be better to use them, since (I admit) memory palaces don’t give you transferrable chess knowledge. (Memory palaces store the exact moves in your repertoire in notation; they don’t train your pattern recognition in similar positions.) On the other hand, maybe it is better to save the 9 hours and invest them elsewhere. I expect the latter is true. As I say in the essay below, ‘this is an empirical question, and there is only one answer that matters: the one that works best for you’.

In Chapter 7 of my book, I include an essay on the question Why memorise theory?. I have decided to publish it online below, to set out my thoughts in more detail.

Why memorise theory?

The Chess Memory Palace method raises some funny possibilities. You could examine a repertoire written in picture notation, memorise it completely, and then know the moves without ever having played them at the board. You could even write a computer script to generate the top engine move for all common lines in an opening,2 convert them automatically into picture notation, then memorise the tree diagram. You would carry a complete world class repertoire in your head, yet your moves would be equally surprising to you as to your opponent!

Is this a good idea? Of course not. Opening study is more than memorising moves. We need to know the typical middlegame strategies and tactics, and the typical endgames, so that we can continue to play a good game at the end of our memory palaces. We need to know the purpose behind the opening moves, so that we can exploit our opponents’ mistakes if they exit our memory palaces unexpectedly early. And we need to know similarities to other openings, so that we can create analogous plans when we need to.

To quote GM Garry Kasparov, “Long before a player becomes a master he realises that rote memorization, however prodigious, is a far cry from understanding. He’ll reach the end of his memory’s rope and be on his own in a position he doesn’t really understand."3

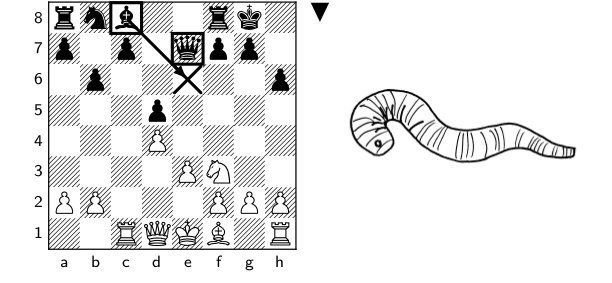

I am reminded of the game Magnus Carlsen v Bu Xiangzhi, from the 2017 World Cup in Tbilisi.4

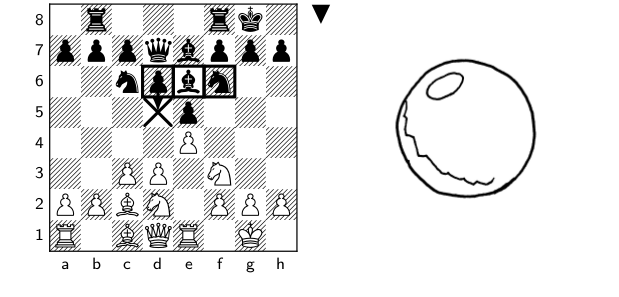

Here, Bu played pearl (…d5), sacrificing his pawn on e5 for a strong – and eventually winning – kingside attack. His plan clearly drew lessons from understanding the Marshall Gambit, despite Bu not being a regular Marshall player.

However, some authors go too far and claim that memory is unnecessary, as long as you understand your openings. The idea seems to be that if you truly, deeply understand a position, the moves will naturally flow out with no memory effort required. This is a mistake. There are two reasons why memory is vital.

First, of course, time pressure. In an exam, a talented student with a strong understanding of mathematics could derive the quadratic formula from scratch. But nobody does this. We memorise the formula instead, which saves time and mistakes when the clock is ticking. The same is true of chess moves.

After a year without review, GM Viswanathan Anand remembered only the smallest fragment of his World Championship preparation when he unexpectedly needed it against GM Levon Aronian (to win brilliantly at Wijk aan Zee 2013).5 Despite knowing the evaluation and a hint of his preparation, and doubtless understanding the position better than anyone else could, it still took him half an hour to re-calculate the right moves. For the rest of us it would have been impossible – unless we could recall them from memory.

Second, there are different levels of “understanding”, and we can often make more progress by using memorised moves as a reminder of our plans, rather than the other way around. In language, we all understand more words of our mother tongue than we use, or are even able to think of. Our “reading vocabulary” exceeds our “writing vocabulary”.6 And yet, we do understand these words when we hear them. The sound of the word triggers our memory of what it means, even though we could not have generated the word ourselves. In the same way, we can read a move from a book or memory palace and then recall its purpose. (“Five? Oh of course, I play ...Kh8 here to make room for the knight on g8, then I can push the f-pawn!") The move itself is a memory aid that triggers our understanding of the position. In other words, understanding and memory are complements, not substitutes.

As we improve, more and more of our moves will be played from a deep understanding of their purpose, without struggling to remember them. But this just pushes the limit of our deep understanding later into the game. There will always be marginal positions, just on the edge of our knowledge, where we don’t understand the position deeply enough to reliably generate the best move – and yet, after being told the move, we can remember exactly why it is important and why we should make it. To play a tactical line of the Schliemann purely from “understanding” rather than memory, you would need to know, understand, and evaluate all the variations. At some point the only practical option is just to memorise the moves.

To take this a step further, I could even argue that in practical play you need to understand the plan going forward, which is not the same as the purpose of the move when you made it. In the position below, from the Tartakower Variation of the Queen’s Gambit Declined, Black usually plays leech (...Be6). On e6, the bishop still has prospects on the c8-h3 diagonal, while also supporting Black’s queenside play.7

But why did Black play ...b6 earlier? To make room for the light-squared bishop on b7! At the time, with more pieces on the board and more central tension, this made sense.

Do you need to know this? In one sense, yes. To understand the Queen’s Gambit and its variations, especially when White deviates early, you need to understand your moves.

But practically speaking, no. If you can reliably get past this point in your games by memory, the important question is what purpose the pawn serves now: does it support c7-c5, or is it just a weakness? If a move creates a threat that never materialises, and your game progresses beyond the possibility of the threat, the past existence of the threat is no longer relevant.

This is particularly clear in tactical openings. Returning to the Schliemann, the Transit Line repertoire in Chapter 4 navigated past several traps and potential blunders. Part of the purpose of White’s moves was to avoid these tactics. Do you need to know what you avoided? Ideally, yes, that would improve your chess understanding. But we have limited time. At the margin, your time may be better spent analysing master games and typical endings, not over-analysing the early opening moves where you already played perfectly. Like following signposts through a swamp, if you can navigate to the end, you don’t need to know what pitfalls you avoided. You need to know where to go next.

Ultimately, whether you agree with this last point or not, it is clear that players spend a lot of time memorising opening theory, yet frequently forget old analysis. Although Kasparov (correctly) emphasises understanding, he certainly wouldn’t deny the value of a strong opening repertoire. In fact he played the Mieses Opening (1.d3) against the computer Deep Blue just to avoid its opening book.8

So you need to memorise theory. The next question is, how? The traditional method is to drill moves from diagrams, perhaps with spaced repetition. Even masters can find this challenging, particularly when trying to learn many similar but different lines at once, when none of them have emotional salience (such as a painful loss).9 In this book I have advocated picture notation in a memory palace instead.

Which method is better? This is an empirical question, and there is only one answer that matters: the one that works best for you. Try both and see which creates the stronger memories. To my mind there is no doubt that, for most people, after a bit of practice, a memory palace is better for creating unambiguous memories that last.

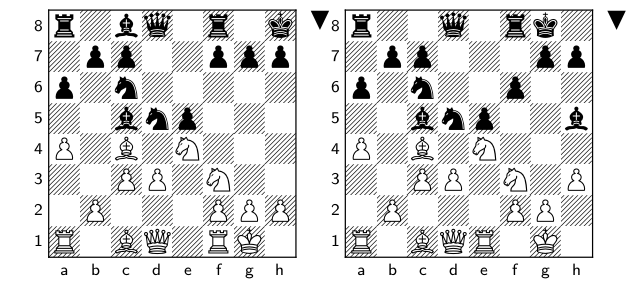

I emphasise unambiguous because a lot of positions are frankly quite similar, especially when you haven’t reviewed them for a long time. The two diagrams below are from different variations of the Italian Game. In one, GM Jan Gustaffson recommends ...Ba7, and in the other ...Bb6. Which is which?10 Even Gustaffson admits this is confusing!

After being told the move ...Bb6 or ...Ba7, I can recall its purpose, but it is hard to work out and be confident at the board. It is much easier using picture notation in a memory palace, when there is no similarity and no confusion.

To summarise, The Chess Memory Palace method does not replace your need for chess understanding. “After a while, I began to notice something”, wrote GM Matthew Sadler after trying to win every game through the sharpest lines, “I was losing lots of games in ‘unimportant variations’.”11 Instead, The Chess Memory Palace method is like printing out your repertoire in notation and reading it at the board. It won’t help you understand chess better,12 but it will let you play your prepared lines with perfect accuracy.

If you had your moves written on a physical sheet of paper, you would be disqualified for cheating. The Chess Memory Palace method lets you achieve this in your head.

-

Ben Johnson’s Perpetual Chess Podcast, episode 364 – GM Patrick Wolff, 9 January 2024. (Added to this blog post in an edit. There are several more such quotes from IMs and GMs in the epigraphs of the book.) ↩

-

computer script: BookBuilder, launched by Alex Crompton in July 2022, is an interesting project that automatically generates chess opening repertoires. It uses the Lichess database and computer evaluations to build a repertoire against the most popular lines. https://github.com/raccrompton/BookBuilder ↩

-

“Long before a player”: Garry Kasparov (2007) How Life Imitates Chess. William Heinemann, page 143. Kasparov does also say that “opening sequences […] are indeed memorised”, and that he plays by “relying on memory to select the opening lines I prefer until I run out of book and am on my own”. Garry Kasparov (2017) Deep Thinking. PublicAffairs. This does not contradict his comments on understanding; instead it reinforces the point that understanding and memory are complements. Kasparov plays a move from memory – but he understands its purpose. ↩

-

Magnus Carlsen v Bu Xiangzhi: Magnus Carlsen v Bu Xiangzhi, 9 September 2017, World Cup, Tbilisi ↩

-

win brilliantly: Levon Aronian v Viswanathan Anand, Tata Steel Group A, 15 January 2013, Wijk aan Zee. Anand’s account of this moment can be found in Viswanathan Anand (2019) Mind Master. Hachette India, Chapter 3 ↩

-

reading vocabulary: Gwern Branwen. Spaced Repetition for Efficient Learning. https://www.gwern.net/Spaced-repetition ↩

-

On e6: John Cox (2011) Declining the Queen’s Gambit. Everyman Chess, page 13 ↩

-

played the Mieses Opening: Garry Kasparov v Deep Blue, 6 May 1997, IBM Man-Machine, New York. Similarly, Kasparov played 7.g4 against the computer Deep Junior’s Semi Slav Defence, because he knew it was not in Deep Junior’s opening book. (Garry Kasparov v Deep Junior, FIDE Man-Machine WC, 26 January 2003, New York; according to David Shenk (2006) The Immortal Game. Doubleday, Chapter 11.) Kasparov preferred to leave Deep Junior’s preparation early, which demonstrates both the value of memorised moves (Kasparov wanted to avoid the book moves) and the importance of understanding the subsequent middlegame plans (now the computer needed to find moves for itself). ↩

-

many similar but different lines at once: There is an interesting account of this in Viswanathan Anand (2019) Mind Master. Hachette India, Chapter 3 ↩

-

Which is which: The answer is …Ba7 on the left diagram, …Bb6 on the right diagram, according to GM Jan Gustaffson’s Grandmaster Repertoire against the Italian Game, on chess24 ↩

-

“After a while”: Matthew Sadler (2000) Queen’s Gambit Declined. Everyman Chess, page 113 ↩

-

won’t help you understand chess better: Apparently there was an experiment demonstrating how chess memory (through mnemonics) can be separated from chess understanding, but I have not yet been able to track down a copy to verify its contents: Ericsson, K. A. & Harris, M. S. (1990, November) Expert chess memory without chess knowledge: A training study. Paper presented at the 31st Annual Meeting of the Psychonomics Society, New Orleans ↩