Reflections on Peter Kropotkin's Memoirs of a Revolutionist (1899)

When Pëtr Kropotkin (1842-1921) was a boy, his tutor used to show him the houses of notable writers in their Moscow neighbourhood. Keeping this tradition, if you walk down Crescent Road, a nondescript street in Bromley, southeast London, you will come across a blue plaque on house number 6 declaring Prince Peter Kropotkin, Theorist of Anarchism, lived here.

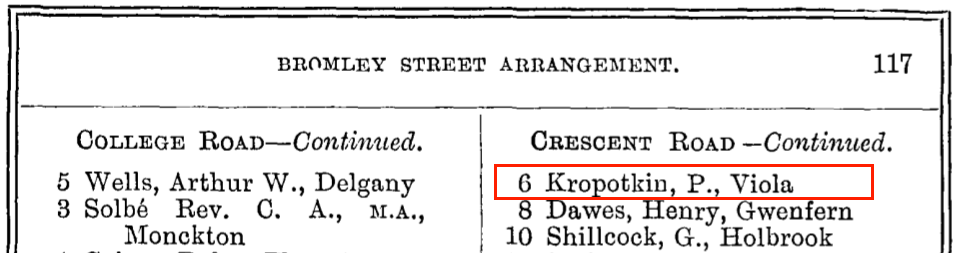

I am not sure Kropotkin would be pleased to be called Prince. He dropped the title aged 12, inspired by the French Revolutionist Count Mirabeau who opened a shop simply enscribed “Mirabeau, tailor”. Kropotkin’s address can be seen in the 1900 Bromley street directory:

Viola must be the name of the house

While Kropotkin lived in Bromley, he wrote Memoirs of a Revolutionist (published 1899). Although Kropotkin doesn’t explain his anarcho-communist philosophy in Memoirs – that can be found in other material such as The Conquest of Bread – we do see where his worldview came from. Kropotkin always had a strong compassion for the Russian serfs. He also had lifelong bad experiences of government. These begin quite surreal:

“Do you know that Chernyshévsky has been arrested? He is now in the fortress.”

“What for? What has he done?” I asked.

“Nothing in particular, nothing! But, mon cher, you know, — State considerations! … Such a clever man, awfully clever! And such an influence he has upon the youth. You understand that a government cannot tolerate that: that’s impossible!”

And of course they reach a climax when he joins the secret Circle of Tchaykóvsky in St Petersburg. Kropotkin spread socialist messages among the peasants while being hunted by state police, under a government that accepted no dissent. Eventually he was caught and held more than 2 years without trial. (Until he escaped. In the most famous part of the book, he then hid until evening in one of St Petersburg’s best restaurants, where nobody thought to look.)

Kropotkin’s mistrust of government was not only about suppression, but also corruption and bureaucracy. I particularly enjoyed one anecdote:

In 1859 the Chitá people wanted to build a watchtower, and collected the money for it; but their estimates had to be sent to St. Petersburg. So they went to the ministry of the interior; but when they came back, two years later, duly approved, all the prices for timber and work had gone up in that rising young town. This was in 1862, while I was at Chitá. New estimates were made and sent to St. Petersburg, and the story was repeated for full twenty-five years, till at last the Chitá people, losing patience, put in their estimates prices nearly double the real ones. These fantastic estimates were solemnly considered at St. Petersburg, and approved. This is how Chitá got its watchtower.

Anarcho-communist poster in East London, January 2022

But my favourite part of the book was Kropotkin’s adventures in Siberia. There are plenty of exciting stories of navigating the Amúr River, expeditions into Chinese Mongolia, and a mad 2000 mile dash from the Amúr to Irkútsk to prevent a famine (followed immediately by an even longer journey all the way back to St Petersburg to report). I will never discover new paths through the Siberian mountains, but it did inspire me to survey some local road surfaces for the Open Street Map.

One satisfying historical note is the discovery of Arctic islands. Kropotkin read “in an excellent but little known paper on the currents in the Arctic Ocean” that ice flows suggested the existence of Franz Josef land (before its discovery). He then writes:

the archipelagoes which must exist to the northeast of Nóvaya Zemlyá – I am even more firmly persuaded of it now than I was then – remain undiscovered.

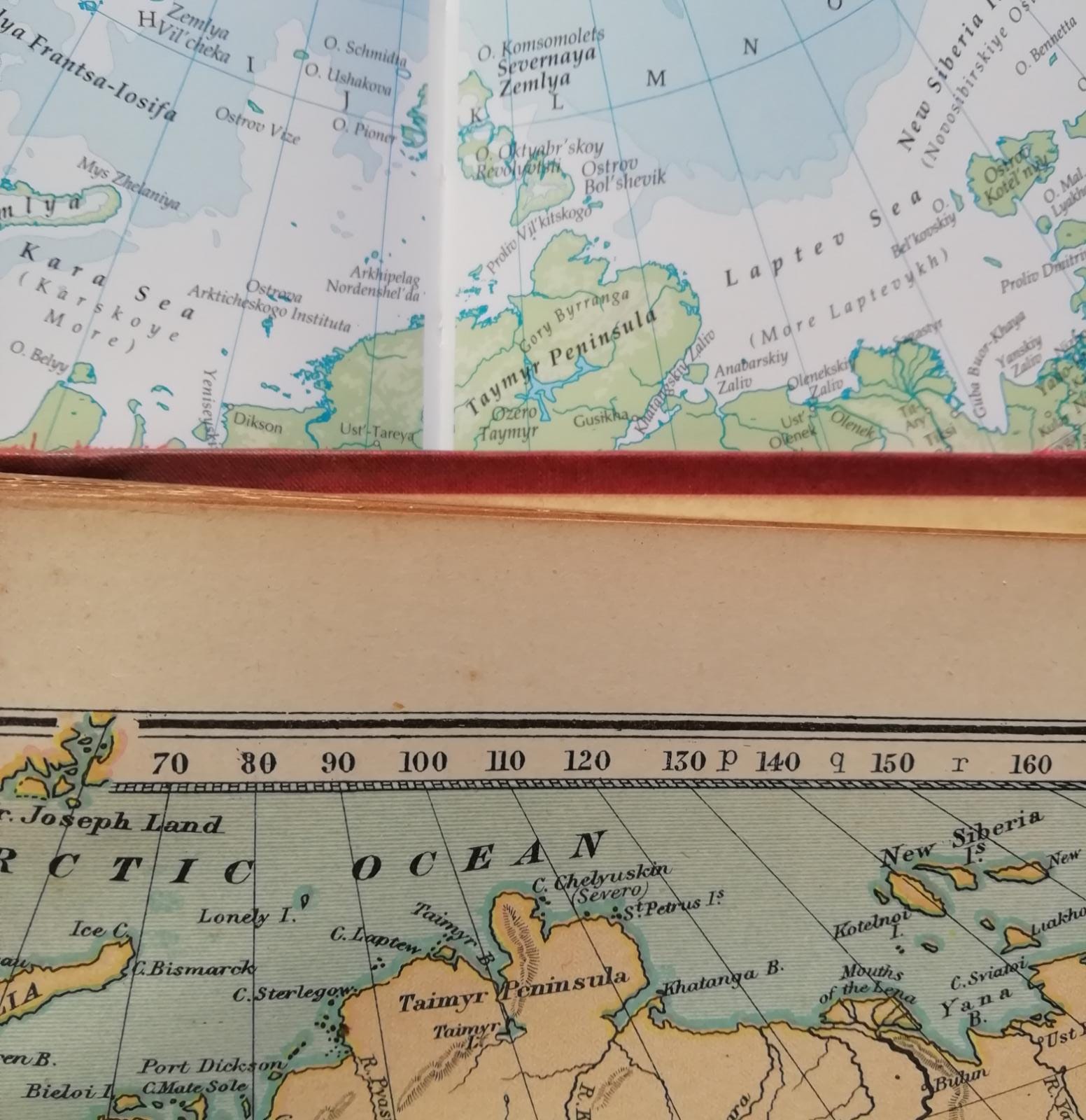

He was correct! The Severnaya Zemlya islands were sighted in 1913 and finally explored in the 1930s. They were given suitably revolutionary names: the three largest are October Revolution Island, Bolshevik Island and Komsomolets Island (from the Communist Union of Youth). Following the breakup of the Soviet Union, many revolutionary names were changed back – Leningrad returned to St Petersburg, Marx and Engels Streets disappeared – but these islands kept their names. Presumably they didn’t have pre-Soviet names to revert to.

Severnaya Zemlya islands, Bacon’s Popular Atlas of the World 1898 (bottom) compared to The Times Reference Atlas of the World 2015 (top). Note also the change in shape of the New Siberian Islands to the east.

In addition to a Siberian mountain bearing his name, and a glacier in Severnaya Zemlya, today Kropotkin is remembered by a mountain peak in Antarctica. From Wikipedia: “Mount Kropotkin is a peak on the west side of Jøkulkyrkja Mountain in the Mühlig-Hofmann Mountains of Queen Maud Land, Antarctica.” In other words, a Russian name within a Norwegian name within a German name within an English name. Born in Russia, Kropotkin’s travels took him to Germany and England, but his plans to charter a Norwegian ship (to explore the Arctic) were frustrated. So perhaps this is a fitting tribute.